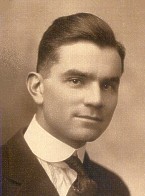

A Genesee Man Share His Reminisces

By Henry Lorang

(Taken from The Genesee News January 12, 1968)

That time would take one back to the 1917-18 era when all of Western Europe was facing a common formidable foe at the command of Kaiser Wilhelm of the German Empire who dreamed nothing impossible by overcoming nation after nation to the eventual conquest of the Western Hemisphere.

When the United States declared war against Germany on April 6th, 1917 I was attending the Northwestern Business College to take a business course along with some newly made friends in Spokane who had come from country towns in Idaho and Washington. Well, We registered for the draft on June 5th but decided to finish our various courses which earned us diplomas at the end of the semester just before the “Fourth of July” vacation. Then we decided to go on back home to celebrate and then help with the harvest while awaiting our draft-call and to meet again in Spokane after fall work on the farm to decide what we would do.

In the meantime we learned that our “numbers” for call were not due until in early to mid 1918 and mine was due for call on May 15th, so with the vast demonstrations of soldiers marching up and down Riverside to the tune of brass bands and rattling drums, we felt the urge of patriotism and decided to enlist together and did just that on December 11, 1917 and left for Kelly Field Texas on the following December 15th. Being advised not to take anything along to camp with us, we sent our suitcases home with surplus accessories and went in our civilian suits and coats and a few toilet necessities headed for Texas in a troop-train with hundreds of raw recruits from The Inland Empire. Christmas came while we were living in the tent-city known as Kelly Field and on that day we had our dinner of turkey and all of the trimmings, sitting out in the open in a swirling dust-storm that made our mashed potatoes look as if it were covered with pepper, but who cared? We were going over to whip the “Heimies-.” After a short time, Kelly Field was stricken with influenza (flu) and the entire tent city camp of 40,000 men was evacuated to clean the place up and build permanently to carry on.

Our contingent was sent to Camp McArthur, Waco, Texas, and here we lived in barracks, and little by little were taught the rudiments of a soldier and how to march to drill commands while also being given regulation army clothes to replace our “civvies” which, by now, were a sorry mess of shoddy suits. We were lined up single-file and marched to the quarter-masters warehouse where a supply Sergeant stood at the door and as he sized you up and yelled out sizes to the men inside “like 36-42 and long or short” suits came flying out at you to catch and then shoes which were called out by the sizes of 8 to 12 as you kept on the march ahead. There was no grumbling.

You just took what you got and traded around until you found a suit that was not skin-tight and yet didn’t flap like a tent and with shoes it was the same, but there were no left or right shoes. And if they were a near fit at all you broke them in to suit by greasing and softening them up. There were hats, too, known as “campaign-hats” made of felt with stiff brim and had chin-straps to counteract the winds. And to fill the gap between the tight pant’s legs and the shoes, there were canvas leggings which laced up on the outer sides of one’s calves down to the buckled strap that held them down over the shoe-traps. We were known as Rookies, and looked the part compared with the tailored suits that were worn by men of the “Standing Army.” The jackets, pants, and coats fairly bristeled with the long wool of old sheep and goats that was used by the tailors who had the task to suit-up millions of men at short notice.

The first of our fighting men went to France on June 26, 1917, but naturally the raw recruits, who had to be clothed and trained, followed in sequence, and our outfit, the then organized 247th Aero Squadron, went in probably by late February 1918 in a convoy of ships escorted by the “battle-wagons,” on the U.S.S. Celtic. All was hush-hush of course and there was no writing home from anywhere except on the printed post-cards given out, one to each man and not one word was to be written except the name and address to whom sent, and these cards were gathered en-masse and mailed from New York Harbor, our post of debarkation. My memory fails me as to the printed message but it probably read “Somewhere over there.”

We had learned a number of songs and our favorite probably was “Good-bye Broadway, Hello France, We’re Ten Million Strong, Goodbye Sweethearts, Wives and Mothers, It won’t take us long. Don’t you worry while we’re there. It’s for you we’re fighting for. And we’re going to win this dog-gone war” or similarly. Every boy and girl recited the little ditty: “Kaiser Bill went up the hill to lick the boys in France; Kaiser Bill came down the hill with bullets in his pants.”

Three of us boys went to England where I was a “sailmaker” and my work was to sew on the cloth to the wings and fuselage, and to paint them with “dope” as it was known, a poisonous, quick-drying paint made from liquid celluloid.

I was in Northern France when the Armistice was declared and the French went wild as they got down on their knees to kiss the American flag hysterically as they shouted over and over, “Vive l’Amerique-Vive l’Amerique, Vive la France.” From now on it was going home which was no less anxious but more subdued and the highlights of my homecoming was to land by train at Spalding, Idaho where I was met by my family and that of my sweetheart, Marguerite and the Tobin family but I don’t recall the date of that happy time.

What a half century since then!

January 6, 1968